- Home

- Carol E. Anderson

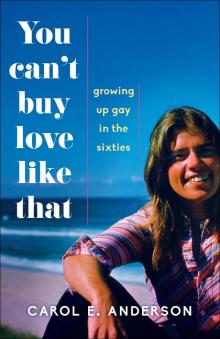

You Can't Buy Love Like That Page 8

You Can't Buy Love Like That Read online

Page 8

Back in my room, their words churned in my head. I feared telling Nicky the details because it would show what a coward I was, so I summarized the gist of it instead. I remember that we stood with arms around each other and cried. It was hard to look her in the eye; I was fearful she would know that I had betrayed our love in an effort to protect us both. She spent the few remaining nights before her father came to get her in her own room.

I helped her dad carry her things outside to his car, and Nicky came down with us on our last trip with the boxes. “Thanks for taking such good care of my little girl,” Mr. King said as he got behind the wheel. Nicky and I leaned into each other as we hugged goodbye; the imprint of her hand on my back left an invisible tattoo.

“I love you,” I whispered.

“I love you, too,” she said, and then she stepped away and got in. She reached her hand out the window, and our fingertips brushed against each other as the car pulled away.

Instead of returning to the dorm, I walked down to the railroad tracks where we used to walk together, dazed and bereft about all that had happened between us, the power of our feelings, the agony of this secret, and the indignity induced by the confrontation by my peers. I told myself this was for the best and that we would both go on to marry guys like we were supposed to, looking for, in them, what we had found in each other. Head down, staring at the rails, I trudged, tears splashing on my boots, until the sun went down and I made my way back to the dorm in the dark, wondering how I could ever live an authentic life in a society that demanded me to lie in order to survive.

chapter

7

in the wilderness

Somehow, I made it through the remaining few weeks until school was out in mid-April, and I went home to my summer job in Detroit Diesel’s secretarial pool. The RAs’ confrontation continued to haunt me. Their words, a constant echo in my head, brought bouts of anxiety. When their voices subsided, Reverend Mitchell would take over with his threats of hell and damnation. Walking into the women’s lounge on a break one day, I heard colleagues laughing at a joke: “What do you call a lesbian who lives up north?” Everyone looked up, smiling, but no one guessed at the answer. “A Klondyke,” said the joke teller, laughing out loud. I sat down and opened my book, not knowing if they were trying to send me a secret message or if they were just revealing their own prejudices. I smiled along, sure to let them know I was one of them.

Every time I was called into someone’s office to take dictation, I feared they would fire me because someone had told them that I was gay. If I was at home and the phone rang, I was certain that someone was calling my parents to tell them that I was a lesbian. When total strangers whispered near me on the street, I was sure they were talking about me. Peace eluded me everywhere.

Mike came the first two weekends I was home, and his presence comforted me even though he had no direct knowledge of what I had been through at school. He was solid, always there, eager to help, willing to do anything that made me happy.

Nicky and I talked on the phone, and I made the trip by train to see her at the beginning of May. Our powerful attraction remained in spite of the distance and continued to cause conflicted feelings in me that I did my best to compartmentalize. On this visit we spent the night together in her single bed and cherished the moments we had alone, holding each other in silence, fearful her parents might hear us in their bedroom next door. I worked hard to drive thoughts of Mike out of my head along with the threats of Reverend Mitchell in this small sacred space where our bodies could lie tangled together beneath the sheets and the sweet smell of her skin melted away my fear and anxiety, even if just for a few hours. Each time we parted was like ripping a Band-Aid off a wound, taking part of the scab with it.

By the middle of May, I had come down with mono, too, and had to quit my job. Fear that someone would figure out that I had gotten it from Nicky overwhelmed me. My illness kept me from seeing either Mike or Nicky for a few weeks as the doctor prescribed total rest. Rather than stay in bed, I spent six weeks lying on the beach at Kensington Metro Park, sleeping most of the day. My small consolation was a fabulous tan in time to be a radiant attendant at my brother’s wedding in late June.

I still wasn’t fully recovered when I joined my parents on the drive to Stevensville, where the wedding took place. They dropped me off at Mike’s in Kalamazoo, and the two of us continued the trip in his car. I was happy to see him, hopeful each time we met that the magic I felt with Nicky would one day appear between us. So far it hadn’t.

The small Lutheran church was simple, with a bare wooden stage at the front of the sanctuary that served as the altar. Folding chairs were aligned in neat rows set back from the platform, and makeshift steps were covered in tan cloth so the wedding party could step easily up to the stage where Jim and his fiancée, Laurie, would marry.

My brother rarely dressed up, and he looked both handsome and young in his dark navy three-piece suit with a white boutonniere, his thin neck jutting out from a marginally ironed shirt. He stood self-consciously with his cuffed pants barely reaching his shoes, his wrists exposed at the ends of too-short sleeves, his hands cupped by his sides.

On his way to becoming a chemistry professor, Jim could recite formulas in his sleep, knowing most about the chemical reactions resulting from mixing two compounds in a lab and little or nothing about the chemistry of relationships. My mother was certain he would be the last to marry, not just of her two children, but of everyone she knew. He had never dated in high school, and he didn’t date in college until his junior year, when he took a ship abroad to study in Germany and met his wife-to-be, also an exchange student. When he brought Laurie home for Christmas, I liked her instantly and felt in many ways I had come to know her better in a few visits than I had known my brother after living with him for years.

As one of the bridesmaids, I waited at the front with the others as the organist played “Here Comes the Bride” and felt my eyes moisten as Laurie, beaming, glided down the aisle on her father’s arm, her lace mantilla floating behind her. The music alone was a powerful elixir, inducing an overwhelming desire to have a marriage ceremony myself. I looked over at Mike sitting in the audience and imagined standing at the altar with him one day, the envy of the crowd, his tanned face highlighting his attractive features. Even then I noticed my pride was related to the jealousy of others in obtaining him as a prize rather than my irresistible desire to be with him. He was everything anyone could want. Maybe I would want him too in that way if we just kept at it.

My reverie was broken as a female soloist began to sing a song about love, which was followed by a reading from the Bible. Then the minister began the official part of the ceremony as he addressed my brother and Laurie directly. There was little prelude to speaking the vows, and I listened as Laurie repeated after the celebrant: “I, Lauren, take you, James, to be my wedded husband, to have and to hold, from this day forward, for better or for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish—until death do us part.” Then Jim said his vows, there was a prayer, and it was over. It was such a big promise for such a few short sentences. I wondered whether people realized what they were saying.

We stayed for the reception of punch and cake at the church and then said goodbye to Jim and Laurie and my folks. Mike and I headed back to the parking lot and got into his car. I hadn’t seen Nicky since May, when I took the train to visit. Unable to resist the temptation, since we were only forty-five minutes from South Bend where she lived, I looked at Mike, and in my most persuasive and cheerful voice I asked if we could drive down and see Nicky. It wasn’t on the way home, but that didn’t matter.

Certain she would be there and happy to see me, I didn’t bother to call. The adrenalin had already started to pump at the prospect of even a few hours with her. Mike looked at me with a slight smile and furrowed brow as I kept talking about how much fun it would be. Even I couldn’t believe I was asking him to do this, but I missed her terribly,

and though we frequently talked on the phone, her absence in my life left a void that nothing filled. From his desire to make me happy, he gave in.

Mike backed out of the parking lot and turned toward signs leading to Highway 31 South. I was playful with him in the car, my enthusiasm boosted by his agreement to take a side trip. He was worried I might not be well enough, knowing that when Nicky and I got together, we had a tendency to get fired up. He asked if I was up to it and expressed his concern about a possible relapse. I assured him I would be fine, hardly able to contain my elation when he said we could go. Even with all that had happened, I couldn’t stay away. And outside of school, I felt freer—no one was looking over my shoulder and monitoring my whereabouts.

Forty minutes later we pulled into her driveway. I leapt from the car to her front door and knocked as I hollered through the screen, “Anybody home?”

Mike joined me on the porch as Nicky flew down the stairs. It was evident in her greeting that she was thrilled to see me. She opened the screen door wide and let us in.

Her folks appeared and said hello to us both, and then her mother came over and gave me a big hug before inviting us for dinner. Mike was about to say no when Nicky piped up and asked if I could spend the night, cajoling him to let me stay, given that he got to have much more time with me and she hadn’t seen me in weeks. Mike looked at me and asked what I wanted to do, and though it was apparent he wasn’t crazy about the prospect, I admitted I wanted to stay. Overriding my feelings of duty to him, I suggested I could take the first train back to Kalamazoo in the morning.

I walked him out to the car and reassured him of how much I loved him and that I just needed some time with my friend to catch up. We kissed goodbye, and I went back into the house. Nicky loaned me some shorts and a T-shirt, and after dinner we borrowed her dad’s car and headed for the Howard Johnson motel. We scoped out the scene around the outdoor swimming pool; then I stood watch as she scaled the fence, motioning me to follow. I scrambled up behind her, threw my leg over the top, and lowered myself down. We did things together I would never do alone, and the thrill of being one step outside of sanity was a rush. Once on the other side, we shed our outer clothes and left them in a pile. We had worn bathing suits underneath our shorts, so were good to go for a dip. Nicky went immediately to the deep end and dove into the pool. I didn’t know how to swim very well, so I lowered myself into the shallow end. It wasn’t that warm, and I could feel goose bumps rising on my arms and legs.

“Teach me how to do that,” I said to Nicky as she swam toward me after her third dive. She hopped out on the side and took my hand and led me toward the deeper end, where she showed me how to position myself with one knee on the edge of the pool and the other leg bent in a half squat. “Just lean over and push off with your foot and fall into the water.”

Fall into the water? I thought, Is she crazy? But my pride impelled me forward, and I followed her instructions. Taking in a mouthful, I struggled to raise my head out of the water, yet I was delighted that I had actually performed something like a dive.

Able to stay afloat to the other side, I jumped up out of the water and shouted out a celebratory cheer of success, forgetting that we were trespassing and wanting to remain undiscovered. We raced across the pool, laughing as we splashed water on each other and felt the magic of the moonlight shine on the glassy surface. After a half hour, we got out. Nicky pulled out a towel and slipped it over my shoulders from behind. I backed up just enough to feel her arms slide down over mine. With a firm but gentle tug she wrapped the towel tighter around me so I wouldn’t get a chill. But the shivers I felt couldn’t be quelled with a terry cloth cover. They ran through my body like the current of a river carrying me away to a familiar place.

She put a towel around herself, sat down in a lounge chair, and beckoned me to sit in front of her. She pulled me back until I was leaning up against her—our heads tilted upward toward the sky. Her arms reached across my chest, and she drew me closer as I laid my head back. The night air was cool; the lights of the hotel loomed over the hedges. Mike’s face flashed across my mind, and I allowed the image to drift away. While looking at the stars, the song “How Great Thou Art” came to mind:

Oh Lord my God,

When I in awesome wonder,

Consider all the worlds

Thy hands have made;

I see the stars,

I hear the rolling thunder,

Thy power throughout

This universe displayed . . .

It was the theme song for Billy Graham’s Crusades, sung by George Beverly Shea. I used to listen to it with my dad when it was broadcast on the radio. The shimmering dots of light in the heavens took me back to that verse, and I longed for the comfort it had once brought—the belief that there was a God watching out for us and that his formidable powers would protect rather than annihilate. Now the words seemed more threatening. I closed my eyes and let go of all that came before and all that would come after this single second—aware only of my weight falling into Nicky and the love I felt between us.

I took the early train to Kalamazoo as promised; Mike met me at the station, and we drove to Milham Park. Our preferred meal was a Whopper from Burger King, and we picked up a couple on our way. As we walked toward our favorite bridge, we saw a cluster of baby ducks scramble to get in line behind their mother as she led them to the water’s edge. Each one looked like a handful of feathers on legs as they waddled along. We both burst out laughing at the sight. My time with Nicky made me feel more relaxed, knowing she was okay and that the magic between us was still there. Oddly, Mike got more of me because of my time spent with her. It didn’t make sense, but it was true.

I returned to my parents’ house by train later that evening and on Monday took up my daily ritual of lying on the sand and wondering about the nature of God and why he would make people attracted to each other if they could never be together. Was life just one big test after another? Was he laughing up there at the world’s suffering? Were we all such pitiful sinners that we didn’t deserve happiness, ever? No answers came to console me, and I felt weary not knowing what to believe.

On Sundays I attended church with my parents, as I always had. Returning to that physical structure reminded me how my faith had changed over the past fifteen years. As a small child I did have faith greater than a mustard seed and believed the many Bible stories I was told. The minister often talked of God’s presence in the sanctuary, and I would crane my neck, stare at the ceiling, and look for him hiding in the tiny crevices next to the giant beams that held the roof up, or I would imagine I could feel him floating above the congregation like a stream of invisible smoke.

To have faith meant to believe in things that you couldn’t see—a message I heard at church and at home. My parents’ trust in that invisible force was evident, but my knowledge of how to apply it was lacking; at the age of seven or eight, I had stood confidently on the front porch with my arms outstretched, telling my parents I would stay outside during the tornado warning because I had faith God would protect me should one actually come.

Though the messages of fire and brimstone frightened me, church music brought me great comfort. The hymns “Amazing Grace,” “The Old Rugged Cross,” “I Come to the Garden Alone,” when sung by the congregation, lifted my heart and filled me with peace. When I shut my eyes, I imagined angels spreading a bed of comforters for me. Through music I found a God I could love. I memorized all the names of the books of the Bible and could recite them upon request along with legions of verses from the Old and New Testament.

At night my dad would come and tuck me into bed and say prayers with me. Sitting in the darkness, he would share about how he had strayed from God and how losing his vision was God’s way of bringing him back to the Lord. It made me scared that something like that could happen to me if I drifted; and while he meant it as a life lesson about himself, it created trepidation in me.

As the minister rambled on, I recalled the night

my father got sick. Sometimes I had nightmares reliving the scene as a four-year-old awakened by the creaking of my parents’ bedroom door and the sound of footsteps shushing across the bare floor. My mother was on the phone and spoke in crisp sentences. “We need an ambulance at 12222 Mansfield, between Capital Street and Oshea Park—it is a dead end. Please hurry; my husband is having a convulsion.”

I peeked out of the door and heard my father moan. He was not in the bedroom, but lying on the couch, covered with a red plaid bedspread. Though the light was dim, I could see his body jerk under the covers. My mother scurried around as she tossed my father’s clothes in the suitcase on the bed. She explained that my daddy was sick and they were coming to take him to the hospital. Listening but not understanding, I picked up the whisker brush in his toiletries bag and pushed it around on my face like my daddy did when he shaved. I smelled the sweet scent of the lather, a momentary comfort.

The shrill sound of a siren outside was interrupted by a bold knock at the door. Two men in white coats sprung through. They rolled the stretcher next to the couch and covered my father’s face with a yellow terrycloth towel. My heart pounded faster. A rush of fear raced through the room like voltage freed from a toaster cord. Flickering red lights bounced off our walls. The painting of the farmhouse in the snow over the couch was tilted to one side, and the garish red lights made it look like a haunted house.

My body quivered—not because of the cold, but because of the dreamlike quality of the panic set off inside that made me feel like I was a roaring river tumbling toward a waterfall. The men in uniform wrapped the towel tighter around my father’s head as they lifted him off of the couch onto the skinny stretcher and then wheeled him out of the house and down the stairs.

You Can't Buy Love Like That

You Can't Buy Love Like That