- Home

- Carol E. Anderson

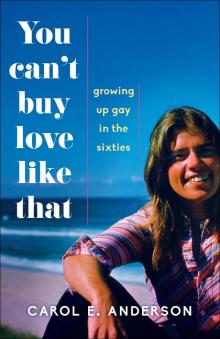

You Can't Buy Love Like That

You Can't Buy Love Like That Read online

Copyright © 2017 by Carol E. Anderson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please address She Writes Press.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

Print ISBN: 978-1-63152-314-4

E-ISBN: 978-1-63152-315-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017942024

For information, contact:

She Writes Press

1563 Solano Ave #546

Berkeley, CA 94707

Cover design © Julie Metz, Ltd./metzdesign.com

Cover photo © Mauree McKaen

Interior design and typeset by Katherine Lloyd/theDESKonline.com

She Writes Press is a division of SparkPoint Studio, LLC.

Names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of certain individuals.

This book is dedicated to my parents,

who loved me well,

and to Archer H. Christian,

the one whose hand I know belongs in mine.

If you can see your life laid out before you,

that’s how you know it’s not your life.

—DAVID WHYTE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

prologue

chapter 1 just as i am

chapter 2 the diet

chapter 3 first broken heart

chapter 4 the blood drive

chapter 5 over my head

chapter 6 pain, pleasure and confrontation

chapter 7 in the wilderness

chapter 8 will you marry me?

chapter 9 road trip

chapter 10 crossroads

chapter 11 women’s liberation

chapter 12 white lilacs for the soul

chapter 13 breakfast at big boys

chapter 14 finding freedom

chapter 15 who wants to be normal?

chapter 16 belonging

chapter 17 the struggle

chapter 18 alone and free

epilogue you can’t buy love like that

acknowledgements

about the author

selected titles from she writes press

PROLOGUE

God loves you even if you are a thief, a murderer, or a lesbian,” the minister shouted from the TV set in the corner of my motel room. I had stopped channel surfing temporarily when an ad came on and suddenly found myself caught in the clutches of a radical Christian station. I stood up and stared at the preacher, his face red and contorted as he thumped his Bible and blasted me across the airwaves. I’d grown up in a fundamentalist Christian household, and his menacing tone was familiar—piercing. I grabbed the remote, and the screen went black.

I turned to the window and looked outside as I slid my Movado watch over my wrist and locked it in place before returning to the dresser and adding other jewelry: gold earrings, a necklace to match, and my favorite black-and-gold bracelet. Blow-drying my hair, I looked in the mirror as I readied myself to facilitate a workshop for a Fortune 500 company at the Marriott hotel in Atlanta. As I studied my face, I could see the small trace of pain that still remained after all these years of learning to love myself in a society that would place me in the same category with a murderer and a thief. It was the 1980s, and I was in my early thirties.

Voices like that minister’s, however faint, remain as haunting whispers even today, thirty years later, as I walk with my partner, Archer, from the parking lot to a performance at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee. It is raining outside, and I watch the couple in front of us as the man leans down and kisses his date on the forehead, slides his arm around her waist, and pulls her closer to him. They walk in step, smiling. She tosses her blonde curls and looks up at him unabashedly in love, then leans her head into his shoulder with a freedom that I envy.

Archer and I walk behind them. She holds an umbrella in her left hand, and I slip my arm through hers to inch closer. I suspect that most people will assume it is to gain the protection of the umbrella against the pelting water. We look straight ahead, cautious of giving a sign that we are gay in an unfamiliar Southern town. We walk in step also, using the umbrella not as shelter against the rain, but as a shield that conceals the barest hint of intimacy, as I squeeze her arm in a silent acknowledgement of love. The urge to slide my arm around her waist is quelled before the thought is finished, an instinctive response to protect her and myself by keeping the nature of our true connection a secret between us and out of view in this public sphere—even though we are legally married in the United States.

While the law officially protects our right to be together, it does not ensure our social acceptance, nor does it protect us from harassment by random individuals who disagree with the law. The neural pathways laid down in the sixties warn us daily to be alert in public places wherever we are—the impulse is so great we needn’t say a word about how we will respond to each other in a new environment. We automatically secrete from others the level of intimacy we share.

This reflexive behavior can engage so readily I don’t realize its source until later—like when my partner and I appear at the hotel counter together to check in and are queried by a pockfaced clerk who is probably about twenty, “Are you sure you want a king room? I can put you in a double.” Or, when I feel the impulse to let go of Archer’s hand when we come upon a group of my MBA students dining at an outdoor café in downtown Ann Arbor, not knowing how my credibility with them might change if they realize I am gay. Or choosing not to reveal to a group of women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that Archer and I are more than friends committed to a common cause, when they ask the point-blank question “Are either of you married?” Each of these encounters represents a risk I feel in my body; my heart quickens, my hands grow cold, and I divert my eyes, assessing and then deciding with split-second precision the level of threat the inquiring person poses and whether it is prudent to conceal or reveal this part of me.

This shaping began for me in innocent ways—in daily doses at my parents’ dinner table, in car rides to softball games, and during Thanksgiving celebrations where I overheard adults in my family speaking in passionate tones about what they really thought about people who were different. Their prejudices slid out past their public Christian personas in ways they didn’t see. My mother was worried about the Armenian man who had moved into the house behind us and wore all black. She was afraid he might harm us, though she had no personal contact with him. My Aunt Bet thought we should treat blacks equally but was sure they wanted to live separately from whites. My Uncle Paul was convinced that people on welfare were just lazy and shouldn’t be given money that they would only spend on cigarettes and beer. Other messages were shouted at me from the pulpit of the Baptist church, where I endured weekly threats of hell and damnation if I sinned, and on the playground in grade school, where boys screamed “stupid queer” at a smaller kid too frail to defend himself, while I watched him run in the opposite direction, eyes turned toward the ground—the laughter chasing him across the graveled surface. Soon I knew what it meant to be okay or not okay in the family, church, and society in which I lived.

I didn’t intentionally absorb these messages. They were burned inside of me like the brand on the side of a steer indicating to whom I belonged and what they expected of me.

Without realizing the exact moment my cellular structur

e was altered by such repeated intrusions into my psyche, I became a prisoner of a way of thinking that demanded allegiance to the tribe into which I was born. I knew what was right and what was wrong, according to the tribal leaders; and if I did wrong, there would be a price to pay. I didn’t know exactly what that price was, but I had a sense it would be bad—and if I strayed from what had been declared acceptable, I had to keep it a secret. All too soon, this way of thinking narrowed my ability to hear alternative and greater truths, ones capable of eclipsing those looming large and ominous in the back of my mind and at the front of my heart. Ultimately I shrink-wrapped myself into an alternate version of me—one that my family, church, school, and country would find acceptable.

Growing up in a fundamentalist Baptist household, my robust indoctrination into Christianity began before I could walk. While my parents spoke more often of God’s love, our minister focused on God’s wrath. And it was his messages that stuck to me like Velcro while my parents’ kinder interpretation of the Almighty slid off like Teflon. Both of my parents had a deep faith in their God and called on him to see them through the tragedies they faced individually and together. The most significant of these was the advent of my father’s visual disability caused by an incompetent physician, which resulted in the permanent loss of my father’s livelihood.

My parents counted on this God to comfort them, to provide financially when needed, and to bring peace when their troubles threatened to overwhelm them. They also subscribed to a belief in original sin and a future home in heaven if you were saved or in hell if you drifted.

Rereading a letter my mother wrote to me while I was in college in 1968, I see how I was bound by the presumed expectations my parents had of me because of their staunch religious beliefs and how I was lost to the love that flowed so freely behind words that threatened my sense of safety. The religious paradigm, so embedded in her character, made it impossible for me to even imagine, in my twenties, that I could have told her that I was gay. At that age, I couldn’t even tell myself.

Today, I hear her voice and see her face—the soft tone of understanding laced with wit, her flashing blue eyes, her half smile—and I imagine her finely shaped fingers typing away on her IBM Selectric while on a work break, thinking of me. I want to reach through the paper and feel the hands that wrote these words, to know in a new way the woman who loved me with a fierce tenderness and a fear that either I was too much or she not enough.

As I read her letter now, I am touched by her words, and I see the broader message she tried to convey; I see how I got stuck on a single sentence that blocked my ability to hear the rest. It was written when I returned to school my senior year in college after a summer home trying to hide my confusion and sadness over losing a woman with whom I had fallen in love. My mother assumed, no doubt, that my unhappiness was about trouble with my boyfriend, Mike.

Dear Carol,

It was good to hear from you yesterday, I needed to talk to you and find out all was well . . . Sometimes I think when we are together we just talk surface talk, never get inside and know something about how the other one thinks. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we just decided to open up our hearts and express the doubts, concerns, as well as current happenings?

. . . We wish we could take some of the sting out of the experiences for you, but this isn’t possible. And through it all, you have been certain of God’s love for you and know that your times are in His hands. We love you with our whole hearts, and want to be your best friends . . .

Take care and always look up!

Love, Mom and Dad

When I received it, I could not let all of her words land solidly inside of me. Right there near the end of it was my dilemma: “And through it all, you have been certain of God’s love for you and know that your times are in His hands.”

I had no such knowing, and, if my times were in God’s hands, I was in serious trouble. How could I tell my mother I was miserable, afraid, and in love with a woman—that people thought I was gay? How could I tell someone so sure I was in God’s hands when I hoped God didn’t really know what I was up to? The letter was not unlike others I had received in my four years at school, filled with references to God, His blessings, and His saving grace. While my mother believed in that God, I was terrified of Him.

Now, I hear great love in her words, her longing to be connected, to ease my pain. As a mother, her intuition told her I was not okay, and she wanted to understand, to help. It isn’t that I didn’t believe that; I just didn’t think she knew what she was asking for and that her response would be to “fix” rather than embrace me. And the rejection I feared compelled me to create emotional distance from her, an act wholly contrary to my natural instincts.

Besides, my mother had had enough to worry about—raising two kids, working full-time, making repeated trips to the hospital to manage my father’s seizures as they experimented with different drugs to bring his system into balance. Her life was hard already, and I didn’t need to add to her concerns by telling her that on top of everything else, she had a daughter who was gay.

I don’t really know what she would have done had I summoned the courage to tell her the truth, to trust that the love she expressed was deeper and wider than I imagined, that she could comfort me when I felt so desperately alone. I just knew I couldn’t risk it.

This was the beginning of trading my authenticity for acceptance. I committed to dating men and carefully monitored my enthusiasm around the women I found attractive and wished I could pursue. I joined with others in making jokes about lesbians to prove I wasn’t one of them. Conversations with others about my life became more shallow and meaningless. I cultivated a strong, confident persona that invited others to share their struggles with me while I hid my own vulnerability. Eventually these actions swept away the possibility of deep authentic connection with many who might have accepted me.

In the late sixties, there was a genuine need for protection. Beyond religion’s promise of eternal life in hell were the broader concerns of living in a society where mental health professionals still defined gay persons as mentally ill—where you could be fired from your job or evicted from your apartment if people suspected you were gay. And most disturbingly, you could be physically attacked without certainty the laws against assault and battery would protect you. These genuine fears expanded my imaginary ones, exacerbating my felt need for safety in all aspects of my life. My protective antenna streamed out to my circle of friends, my cadre of work colleagues, and especially into interactions with strangers. Over time, I built an invisible shield between myself and others. My ability to alternate between a public persona consistent with the norms of the culture and a private life consistent with my authentic self became as seamless as donning a winter coat to protect my skin against the chill of harsh weather.

Now, decades later, it occurs to me that the danger of revealing my secret may not have been as great as I imagined, and the cost of keeping it may have been far greater than I could calculate.

chapter

1

just as i am

My parents’ radical faith in God persisted through hard financial times and even the illness that befell my father when I was a child—devotion they expressed by attending church services every Sunday morning, every Sunday evening, and, often, prayer meeting on Wednesday night. If you looked up Baptist fundamentalism in the dictionary, the definition would probably start with, “Thou shalt not,” as it related to any form of physical pleasure, or even the occasional delight in a sideways glance at the beauty of the human form. There was no drinking, no dancing, no smoking, no card playing, and certainly no touching of another person by anyone for any reason other than by accident, maybe in an elevator.

Our pastor, Reverend Mitchell, was in his early fifties, and his snow-white hair (flowing back in waves, parting in the middle like the Red Sea) made him look to my young eyes like God himself in a business suit. He was a handsome man of average stature, with a booming voice t

hat rose to the ceiling, bounced off the rafters, and reverberated down the aisles as he bellowed from behind the solid oak pulpit. His consistent message included three main themes: Christ died for your sins and would be back to reclaim his own; you had a choice between heaven and hell; and you should accept Jesus today to wash your sins away. Each point was hammered home with a force that made me fear God might strike me dead before the service was over. I wondered how it was possible to be in this much trouble just for being born.

This view made it hard to reconcile stories of a loving God with someone who would have you burn in hell just because you snuck out of the house to see Bambi at the Atlas Theater with the neighbor kids or put a blotch of ink on the back of Annie Stanel’s sweater when you sat behind her in fourth grade. I remember my nervousness when I went home that night after the sweater blotch, fearful that God would call the principal himself, resulting in my banishment from Coolidge Elementary School forever. In the Baptist church, it seemed that every unfortunate thing that happened to you was linked to sin—my father’s illness, losing my favorite ring, coming in second in the Bible School poster contest. Anything that didn’t work out the way I had hoped was most likely due to a moral failing on my part.

Those damning images seared their way into me and became a part of my religious DNA.

Reverend Mitchell ended every service by imploring people to repent. “Now is the time to accept Jesus,” he would say softly as the organ music played “Just as I Am” in the background. I hated this part; staring at my best patent leather shoes, my toes tapping impatiently inside my best Sunday footwear, I wanted to dart down the aisle in the opposite direction and bolt from the building.

A hush would come over the congregation, and heads would bow as the music director led us in this closing hymn—a final entreaty for lost souls to come to Jesus. “Who wants to be saved today?”

You Can't Buy Love Like That

You Can't Buy Love Like That