- Home

- Carol E. Anderson

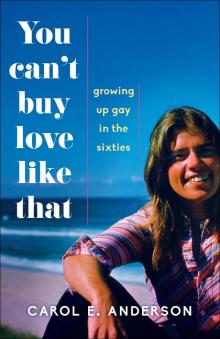

You Can't Buy Love Like That Page 13

You Can't Buy Love Like That Read online

Page 13

chapter

11

women’s liberation

I returned from my trip in September 1974, resumed my old job as a teacher at the Danbury School of Business, and enrolled in undergraduate statistics and experimental psychology at Eastern Michigan University. During the first semester, I lived in an apartment complex near my parents and spent most of my time teaching, studying, or going to class. Then I rented a room in an old sorority house in Ann Arbor for the winter semester. Though it was farther from both school and work, I had wanted to live there since I had dated a guy who attended the University of Michigan years before.

Thankfully, I passed Statistics and Experimental Psych and applied to the graduate program in School Psychology the same day I received notice. Living in Ann Arbor would make it easier to hang out with my new friends, Pat and Kathy, both of whom were Ann Arbor residents, and I was eager to spend more time with them. We all shared a rowdy streak that brought out the crazier part of each of us—in a good way. They also introduced me to many of the previously forbidden pleasures of life, starting with instructions on how to smoke dope.

“Move over,” Pat said. “Here’s how you do it.” She sank into the couch next to me, leaned toward the coffee table, scooped up the finely crushed marijuana leaves, and spread them evenly in a narrow line at the edge of a small square of white tissue-thin paper. With one expert motion she rolled the whole thing into a perfect slender cylinder. “There—see how easy it is?” She pulled the joint to her lips, struck a match to the tip, and inhaled. The smoke swirled thick and pungent into the air as she forced what was in her mouth into her lungs. Handing it to me, she gestured for me to hold it up to my lips while she struck another match. This brought back memories of sitting with Gina on the picnic table in O’Shea Park the first time she offered me a Pall Mall cigarette. I knew better now than to suck on it like a straw; but I had never smoked dope before, so I handed it to Kathy to watch her technique before I took a toke. No one in my previous circles of friends smoked marijuana, and though I knew it existed, I had only a faint notion of the possible effects. None of how life was supposed to turn out had worked for me so far, and after my travels, little phased me about the secular world. I had no qualms about getting high with my new pals just to see what it was like.

Soon we were rolling on the floor in laughter, mocking Dr. Miesel, our psychopathology professor, who fancied himself to be a miniature Dr. Freud—dressed in his tweed jacket, vest, and gabardine pants, his beard finely manicured and cut close to his face. He was short with thinning hair he parted on the left, just like his idol, Sigmund. In class, he would strut back and forth in front of the room, his left hand on his hip, his wire-rimmed glasses balanced precariously on the end of his nose. If he could have smoked a cigar in class, I’m sure he would have.

Both Pat and Kathy were enrolled in the clinical psychology program but we had overlapping classes. Pat was in her late thirties with three kids aged seven to thirteen. Kathy was three years older than I and had a three-and-a-half-year-old daughter. Both were returning to school to follow a dream deferred. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I was returning to school to find myself. Both Pat and Kathy were divorced and, like me, caught up in the excitement of the women’s movement careening through the seventies like a kayaker sliding down a waterfall. Ann Arbor was famously a bastion of liberal activity spawned by student activists who championed change not only at the university but also in the city itself.

It was like moving to a new country compared to my sheltered life in Detroit just forty miles east. For many women, a fierce restlessness had been building for decades. And when Kate Millett, in her groundbreaking book Sexual Politics, articulated the oppression that women had experienced for generations, it unleashed a torrent of rebellious energy across the continent. The fact that her book sold eighty thousand copies in its first year, when one had to drive to a bookstore to get it, was an affirmation of how thirsty women were to hear a female version of the truth.

Pat was definitely into men, and Kathy was, too, hanging out with a political activist named Andrew. Both were becoming staunch feminists whose politics were on the far side of liberal, and we spent a lot of time talking about the articles in Ms. Magazine or the latest book on women’s issues. One we read together was Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown—a fictional story about a self-possessed lesbian character who was strong-willed and brilliantly funny. The ease with which these topics were discussed created a comfort in me and a hunger to spend all my spare time with my new pals. I didn’t know what I was anymore, but I began to feel that the “me” crafted by my family and the larger culture was not the authentic one. This environment enlivened my curiosity about everything—racial issues, women’s rights, and, most especially, the possibility of loving women without persecuting myself. Here, I felt safe to begin exploring my attraction to women without the constancy of my internal judge hovering over me. Let Dr. Miesel have Freud; our heroines were Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Germaine Greer, and Kate Millett—women who, in their intellectual treatises on patriarchy and the subjugation of women, were putting into words the things I had long felt.

When I wasn’t teaching, the three of us hung out together, and I eagerly participated in the worldly education I had been denied the first twenty-six years of my life. We explored our new freedom as women, dressed in overalls and plaid shirts rather than skirts and blouses. We refused to wear makeup, to shave our legs, or to wear bras in protest of being viewed as sex objects among a sea of men who couldn’t quite grasp why grown women, most often referred to as girls, felt oppressed. We attended workshops on women’s health, participated in protests, and advocated for equal rights for women in school, at work, and in the home. My mother, who had been excited about my improved appearance after our weight-loss experiment when I was sixteen, judged these new developments as serious regressions. Whenever I appeared in my new attire, her exaggerated eye-rolling would be followed by familiar words: “Oh, Carol, can’t you wear something else?”

A year passed, and Kathy and I became closer—spending more time as a pair, outside the trio we had formed. She was about my height with long, straight brown hair parted in the middle that hung past her shoulders, often hiding a portion of her face on both sides. She read and wrote poetry and had a vocabulary I envied. She asked piercing questions that made me think about patriarchy and the role religion had played for eons in the suppression of women. She was adamant about our rights as females and sought justice for all who suffered at the hands of patriarchal institutions. Kathy had no patience for those who were less intelligent or insightful than she, and that included most everyone in any room she occupied. She challenged me to think rigorously, to question the status quo on multiple fronts, and to take a public stand for the things I claimed to care about. She was a member of one of the few remaining chapters of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a radical activist movement in the United States.

I, myself, had grown agitated about inequality and injustice over the years, as my understanding of prejudice grew—heightened largely through exposure to the riots in Detroit in the late sixties and to the inequality women faced in the workforce. I experienced this directly too—most sharply right after graduation from Western, when my application for an entry-level position at Ford Motor Company was denied. I was outraged when the position was offered instead to a male student who graduated in my same class, while I was given the option of taking a secretarial position at half the pay and with no room for advancement. I was without allies or a way or place to focus my discontent in those years. Now I was surrounded by legions of like-minded women who dared to ask why things were the way they were and who were adept at providing arguments for why they shouldn’t stay that way.

In the spring of 1975, Kathy, Pat, and I attended a psychology conference in Chicago—another first for me. It was a year and a half into my three-year program. After two days of intense workshops and speeches, Kathy and I opted to escap

e the planned sessions on the third day and go to the art museum instead. Taking off in the morning without sharing our plans with anyone, we wandered the streets of Chicago, our conversations occasionally drowned out by the rumble of the “L” train that lumbered overhead. As we perused the gallery’s paintings and artifacts, I felt a familiar buzz when we accidently bumped into each other in passing or when her hand lingered slightly longer next to mine when I handed her a bottle of Pepsi. The racing pulse, the unanticipated flash of joy in being alone together, and the emerging self-consciousness were all signs that we were interested in more than the artwork. The day was filled with the sizzling enchantment that accompanies sexual attraction—each look or smile rich with subtle revelations.

It was emancipating to realize that these waves caused elation rather than drowning me in angst or shame. There was no brooding Reverend Mitchell chasing behind me, nor did I have the faint awareness that, were I to enjoy these feelings, a terrible punishment would descend upon me—that God would leap over the bridge above and strike me dead. I no longer thought I would go to hell for living in a body and enjoying the sensations that went with that. Because I’d been invited in the past year to scrutinize my own and others’ beliefs through class assignments and discussions with friends, a slow but steady transformation had been unfolding. While I hadn’t yet crafted a new paradigm about God and sin, I no longer held the cruel one to which I had been so bound.

Kathy drove on the ride home from Chicago. The juice of our connection flowed through the upholstery from the front seat to the back as I caught her eyes, again and again, seeking mine in the rearview mirror. We dropped Pat off at her house and then went back to Kathy’s. She lived in an old neighborhood where large, shady maples and oaks with voluptuous canopies lined the street and moderately sized homes sat within yards of each other; gardens were showing signs of spring. Though it was May, there was still a chill in the air.

“Would you like to come in?” she asked. “I have one more night of freedom until my ex brings my daughter back.” The house itself was built sometime in the forties or fifties, boasting the elegant charm that solid wood floors, curved archways, and plaster walls brought to even small homes built in that era. The living room was cold, and she asked if I would build a fire as she set about finding us something to eat.

Wadding up the Ann Arbor News into paper balls, I arranged them strategically on the grate in the fireplace and then set slender sticks of kindling to balance across them before adding medium-sized logs and finally the big ones. I opened the flue, struck a match, and touched it to each wad of paper. My well-designed and careful construction did not disappoint as I watched the dry twigs catch fire and the draft up the chimney ignite a frenzy of heat and light. Staring into the flames, I was reminded of Nicky and how she would light a match and watch it burn as she spoke. I could still feel the rush her gaze would cause—so close in spirit and so far from knowing how to nurture such a special love. I wondered what would have come of it had we met here now, six years later.

Kathy appeared from the kitchen with a plate of snacks and then disappeared into the bedroom, returning with an armful of blankets and pillows. We spread them out on the floor and put the plate between us. I wanted to both waltz and race into this moment as I felt a blend of calm and excitement. Kathy had never been with a woman. And though I had, it had never been without the attendant shame. A swell of shyness came upon us both as we studied the plate of food and avoided eye contact. In Chicago, we were most often in the presence of others. Even on our walk around town, we knew we would return to the group. It was fun to flirt, to get close to the edge, but now we were seated on it—and I wasn’t sure if we would fly or fall.

In truth, we floated, lying in front of the fire, feeding each other apples with peanut butter, exchanging long gazes between bites and sips of wine. Kathy brought out a joint, and a few tokes brought a mellow vibe and ease to the conversation that went into the night—we elaborated further on tales of growing up in different social classes, she in Grosse Pointe, an affluent suburb, and I in Detroit, a working-class neighborhood. She came from wealth, I from modest means, her college education paid for before she was born, mine earned through summer jobs as a secretary. She grew up with a stay-at-home mom, I with a stay-at-home dad. Her father was an attorney, my mother a secretary. We were Mercury and Pluto in the distance between our formative realities, yet we were drawn by the powerful magic of attraction toward the sweetness of sensual pleasure in front of the fire all through the night.

I awakened feeling the physical pain of a cricked neck from sleeping all night on the floor but none of the old emotional pain I had suffered in the past when waking up next to a woman. Along with the sunlight spilling through the living room window was a delirious peacefulness that had eluded me for years, and we snuggled closer together, enjoying the freshness of the morning.

Kathy and I continued to include Pat in our escapades, and she was the first person we told of our night together and the feelings we had for each other. This time, I felt eager to share the news—proud to be with someone for whom I felt this budding love without the need to kill it before it had a chance to sprout. Ann Arbor was a place that made that possible, and Pat’s liberal views made it safe.

Shortly after we met, Kathy moved into a cooperative house with two other women. Both of her housemates were jubilant gay women, proud of their sexual identity: Maureen was the lesbian advocate at the University of Michigan, and Theo was in a radical phase of life, living in opposition to anything that could be considered the status quo in America. She claimed to be a political lesbian, a term used to describe women who were not necessarily physically attracted to other women but who were in opposition to being dominated by the patriarchy. Being this kind of lesbian was a matter of principal. Choosing such a path was beyond my understanding, given I had fought so fervently to not be a lesbian of any kind.

Many fascinating women who were part of the cultural movement for change came through that house, bringing with them the most recent feminist articles and notices of female speakers scheduled to be in town in the coming weeks. Small groups of us would talk for hours about the need for equality in pay and employment and, above all, the need to have control over our own bodies.

The same deep emotional bond I had had with Nicky and Julie was available with many women here, with fewer constraints around physical expression. Even straight women acknowledged their attractions to other women in this new world of feminism, not fearing where such attractions might lead. An evening in the Power Center listening to a panel made up of Gloria Steinem, Alice Walker, and Kate Millett left me high for days. Their articulate and elegant arguments on behalf of women’s freedom lifted me to greater consciousness and commitment to live my own life in tune with what was important to me. It began to make sense for women to fall in love with each other.

Also of great significance to me was the emergence of a new genre of music written and sung by lesbians on the recently launched Olivia Records label, founded to market women’s music exclusively. One evening, a woman showed up at Kathy’s house with a surprise. She reached into her back pocket and whipped out a cassette tape. Waving it in the air, she taunted, “Guess what I have? Does anyone have a tape recorder?” We all scrambled around the house looking until someone reappeared with the device. She popped open the slot and slid the cassette inside, then smacked it down and pushed the play button. Even on this bootlegged version of the original record, the sound of Cris Williamson’s voice was piercing and sweet. She was singing about my experience of being a woman—of loving a woman. Her voice went through me with the resonance that only music can bring—instruments playing in harmony carried her melodies across this thin strip of tape like an anthem I had longed to hear from the first moment Gina rolled over and put her arm around me when I was fifteen.

Sweet woman

Rising inside my glow

I think I’m missing you

Singin’ to me them soft

words

Take me to your secret

Letting me know

Take me in

You let it all go

Oh the warmth, surrounding me

This night, staring, staring at me . . .

A little passage of time

Till I hold you and you’ll be mine

Sweet woman, rising so fine

Her affirmation of love for a woman was the psalm my heart had ached for. She sang with passion and tenderness—unapologetically. I couldn’t stop playing the tape, allowing the words to sink beneath my skin, absorbed by my blood and bones, replacing the hymns of my youth with the songs of my future.

chapter

12

white lilacs for the soul

I continued my double duty of work and school through spring semester and into the fall. Generally upbeat and happy to see the students for my evening shorthand class, the heels of my black leather boots clicked against the shiny floor as I hustled to my room—a friendly warning that I was about to arrive. I turned the corner and heard the bustle of my pupils scrambling to find their seats, steno pads, and pens. The whispers slid to a hush as I came through the door. “Hi, everyone. How was your day?”

Jennie, a sassy Italian girl about eighteen years old, boasted, “I took dictation to The Phil Donahue Show today and got most of it. He is such a jerk. He hardly lets anyone talk before he butts in and says his two cents. If I was on his show, I’d . . .”

Before she could finish her story, David, the director of the school, came into the room and made an announcement. “Class is dismissed this evening.” He was stern, though nothing in his voice revealed the reason for his abrupt entry. Had a water main broken? Was a storm brewing? A tornado? Had I done something wrong? Was I about to be fired?

You Can't Buy Love Like That

You Can't Buy Love Like That